ss Bette Midler Breaks Down in Tears as She Honors Diane Keaton at Heart-Wrenching Funeral — “She Lit Every Room She Ever Walked Into, and Now Heaven’s a Little Brighter”!

close

arrow_forward_ios

Read more

00:00

00:00

00:38

Bette Midler Honors “Extraordinary” Costar Diane Keaton After Death

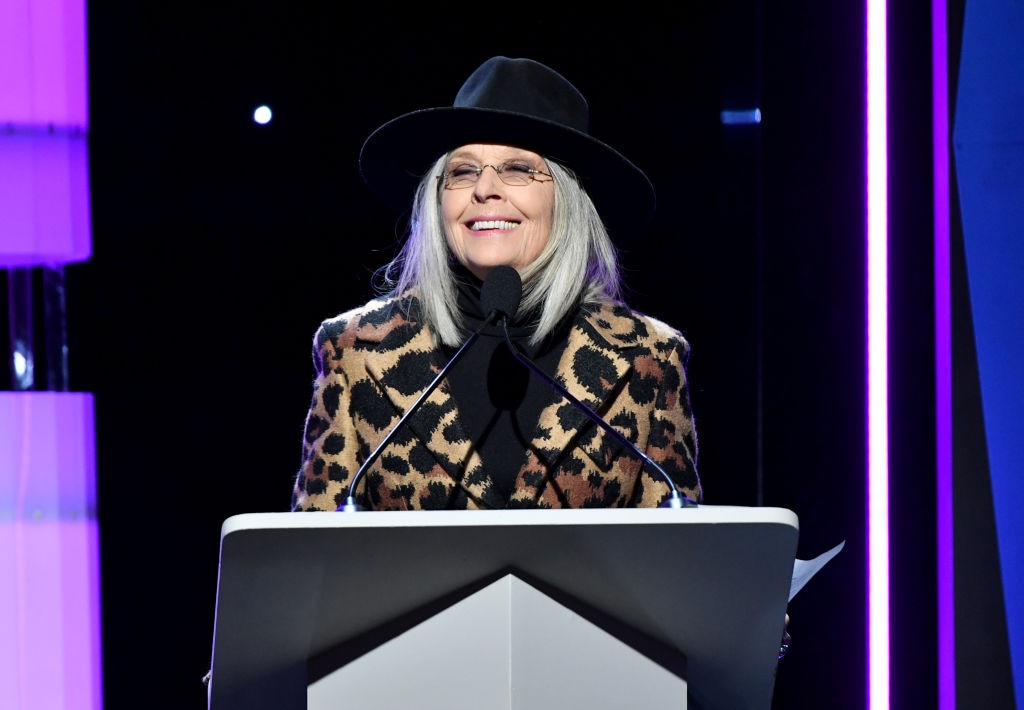

The film world gathered in quiet reverence this weekend to say goodbye to Diane Keaton, the Oscar-winning actor whose singular voice, off-kilter elegance, and fearless choices helped redraw the lines of American screen acting. At a private service in Los Angeles, friends, family, and collaborators celebrated an artist who never merely played a part—she inhabited it. Among the tributes, Bette Midler’s eulogy stood out for its mix of mischief and melancholy, a perfectly Keaton-esque blend that left mourners laughing through tears.

Midler, Keaton’s friend and costar in The First Wives Club, walked to the lectern with a hand on her heart, steadied herself, and began simply: “She was the brightest light in the room—always.” The phrase hung in the chapel like a benediction. It captured what colleagues had long said about Keaton: on a set, at a dinner, in a rehearsal hall, she illuminated everything around her without dimming anyone else. “She never tried to be anyone but herself,” Midler continued, “and somehow that gave all of us permission to do the same.”

The congregation—an intimate roster of legends and loved ones—reflected Keaton’s five-decade reach across genres and generations. Goldie Hawn dabbed at her eyes with a linen handkerchief as Steve Martin, a few rows back, nodded along to Midler’s stories. Leonardo DiCaprio folded his hands as clips from Marvin’s Room played on a silent loop on the chapel’s screen between speakers. Mandy Moore clasped elbows with an old friend from an early-2000s set; a few aisles over, a sound mixer who’d known Keaton since the Godfather days smiled at a memory only he could see.

The program was simple: white cardstock, black serif type, a small photograph of Keaton in a bowler hat on the cover, laughter lines gathering at her eyes. Inside were two quotes Keaton loved: “La-di-da,” of course—an artful shrug to the chaos of life—and a line in smaller type from an interview late in her career, “I’ve never been bored by people.” That curiosity, as many speakers and friends later noted, was the motor behind her art and the glue in her friendships.

Midler’s eulogy, equal parts roast and reverie, traced a friendship that thrived on giggles and the defiant joy of middle-aged reinvention. “We’d ruin takes because we couldn’t stop laughing,” she said, describing those delirious moments on The First Wives Club when the director called cut for the sixth time and the three leads—Keaton, Midler, Hawn—collapsed into one another. “Diane had this childlike delight that never left her. She could make a costume fitting feel like opening night on Broadway.” Midler paused, then added, “And she made aging look like an art form—fearless, funny, and as stylish as ever.”

As Midler spoke, a curated slideshow unfurled—Annie Hall, Something’s Gotta Give, The Godfather, Reds, Baby Boom—intercut with home-movie snippets and Keaton’s own black-and-white photographs. There she was, barefoot in a kitchen, balancing a sketch pad on her knee; there she was, in silhouette against an unfurnished window, measuring light with the side of her palm. The vanity-free intimacy of those images reminded the room that Keaton’s world extended far beyond her filmography. She was a photographer, preservationist, and archivist of her own life, cataloguing little beauties—a dented doorknob, a crooked staircase, the way afternoon light falls on a chipped coffee mug.

One particularly tender clip caught Keaton and Midler in a half-embrace just off-camera, the two of them murmuring about a scene while leafing through a wardrobe rack of cream-colored blazers. The room laughed softly when the slideshow paused on a famous shot of Keaton in her Annie Hall waistcoat and men’s tie. It wasn’t just an outfit; it was a manifesto, a rebuke to the tidy boxes Hollywood assigned women. In that moment, the audience could feel how the clothes, the stance, the voice, the angles—all of it—conspired to make a new kind of screen heroine: smart, screwball, idiosyncratic, alive.

The chapel’s décor spoke in Keaton’s grammar: white roses in low, rounded arrangements; wide satin ribbons left untied; tall glass cylinders of unscented candles; and along the walls, a grid of Keaton’s photographs of Los Angeles architecture—stucco facades, Spanish-tile roofs, a forgotten neon script spelling out “Supper.” Friends said she chose those images for the service months ago—not morbidly, but with the meticulous care she brought to everything. “Even goodbye should be composed,” she once told a friend, “like a shot you love, but don’t force.”

Goldie Hawn rose from her seat during a quiet moment and crossed to the lectern. She reached for Midler’s hand, squeezed it, and then faced the room. “We’re not ready to let you go, Di,” she said, voice trembling. “We had plans—important, silly, necessary plans.” Hawn described the dream many friends share: a ramshackle house by the ocean in their eighties, cracked paint, mismatched mugs, Sunday dinners with children who’ve become unreasonably patient with their elders’ stories. “We were going to be old ladies together in big hats, stealing fries and starting arguments about books we hadn’t finished,” Hawn laughed. “Maybe we still will—just in a different way.”

Keaton’s children, Dexter and Duke, sat near the front, flanked by close friends. The service folded their mother’s private life into her public legacy gently. A family friend spoke briefly about the small rituals that anchored Keaton’s days: a morning walk, a ritual of tea, a stack of photographs laid out on the dining table like tarot. “She loved order,” the friend said, “but she loved surprises more.” Another speaker—the director of photography on a recent indie—recalled how Keaton would sidle up to the camera during lunch, peeking at the monitor to see what the light was doing to a face in profile. “She noticed everything,” he said. “That’s why, when she looked at you, you felt seen.”

The testimonials accumulated into a portrait of a woman who kept expanding even as the industry tried to shrink her. After Annie Hall, she could have coasted on a version of the kooky ingenue forever. Instead, she jumped lanes: political epics, family dramas, prickly comedies, and late-career romances that insisted desire doesn’t retire at 50. She took the space available to her and then built additions—rooms for curiosity, for mentorship, for stubborn delight.

Outside the chapel, fans clustered behind a velvet rope, leaving roses and handwritten notes along a low stone wall. Again and again, the same two words appeared, scrawled in Sharpie on card stock or inked in fountain pen on cream stationery: “La-di-da.” The phrase, tossed off in Annie Hall with an airy shrug, had become a shorthand for resilience—the graceful refusal to be crushed by the world’s absurdities. One note in a child’s tight cursive read, “Thank you for making it okay to be weird.”

Inside, a string quartet pivoted between Bach and a breezy jazz standard; a piano under the balcony filled silence with a few maverick chords. When the time came to close the service, Midler returned to the front and, without accompaniment, began to sing “Wind Beneath My Wings.” The room was still. On the screen behind her, images from across Keaton’s life appeared in slow, steady tempo: a laugh with Warren Beatty on the set of Reds; a quiet moment backstage; a snapshot of Keaton at home in socked feet, a book face down on the couch beside her. The last slide showed nothing but light—the sun tipping through the leaves of a sycamore, the image held long enough to feel like a breath. “Fly high, my friend,” Midler whispered as the final note dissolved. “You’ve always been the wind beneath all our wings.”

In the days leading up to the funeral, tributes had poured in from across the industry: directors remembering an actor who arrived with a mind full of ideas and a willingness to pare them to the truest one; actors honoring a colleague who gave generously in a scene and asked for the same; crew members recalling a star who learned names, asked about kids, and remembered favorite snacks. Some recalled her wry work emails—subject lines like “hat chat” and “architecture chitchat”—followed by meticulous notes on blocking, angles, or props. Others mentioned her unshowy kindness: handwritten thank-you notes, a bouquet arriving after a tough week, a text message that just read, “La-di-da. Call me when you want me to listen.”

Keaton’s relationship with fashion got its own quiet salute. Friends placed a handful of her signature fedoras on a console table near the guest book. No one touched them, but everyone looked—a small museum of choices that once startled and then transformed an industry’s assumptions about femininity. Wardrobe archivists who’d worked with her over the decades used the same words as directors: “collaboration,” “instinct,” “joy.” For Keaton, clothes were architecture for the body: structure, silhouette, surprise. “You build the outside so the inside can breathe,” she’d said in an interview, a line quoted on the back page of the program.

There was, too, a sense of unfinishedness that haunts any life halted mid-project. Keaton had been in conversation about a small, character-driven film, an elder-romance with thorny edges and bright slapstick. There were notes in a journal—ideas for dialogue, a sketch of a kitchen set with a wall knocked out to let in more light. A producer who flipped through the journal in recent days described a margin scrawl that felt like a thesis: “Let them see the wanting.” That was Keaton: unafraid to place yearning—a woman’s yearning—at the center of a story, and to insist it could be messy, comic, and dignified all at once.

If grief is, as some say, the price we pay for love, then Hollywood paid that price in full this weekend. Yet what filled the chapel wasn’t only grief—it was gratitude. Gratitude for an artist who expanded the frame. Gratitude for a colleague whose curiosity raised the game on every set. Gratitude for a friend who made room for other people’s oddities and, by doing so, helped them feel less alone. “She showed us how to be specific without being small,” an actor mused on the steps outside, tucking that program into a blazer pocket as if it were a talisman.

As guests filtered out into the mild Los Angeles afternoon, conversations drifted from reminiscence to quiet planning—Who would spearhead the photography archive? How might the Academy honor her in a way that felt personal, not perfunctory? Could a scholarship in her name help emerging filmmakers who, like Keaton, don’t fit the mold but refuse to sand down their edges? The industry, so often accused of being a machine, felt instead like a neighborhood after a beloved resident has moved on: doors open, casseroles delivered, eyes a little red, humor flickering back to life.

Back at the lectern, a final detail waited for anyone who lingered. Beside the guest book lay a smaller, leather-bound notebook with a single invitation stamped in foil on the cover: “Write something true.” People did. Some wrote about their first Keaton movie—how Annie Hall made them want to dress like themselves, how Something’s Gotta Give made them believe a second act could be more beautiful than the first. One note, penciled in block letters, read: “You made it okay to be brave and ridiculous at the same time. Thank you.”

By sundown, the white roses were thinning and the last of the candles were guttering in their glass sleeves. The courtyard had filled with bouquets from strangers and luminaries alike: gardenias, peonies, chrysanthemums the color of dawn. A young couple posed by the stone wall for a quick photograph, then embarrassed, lowered their phone and simply stood there for a moment, heads together. It felt right. Keaton’s legacy, after all, isn’t only the films she made or the styles she electrified; it’s the small permission slips she handed out, unwittingly, every time she walked on screen: be odd, be honest, be kind, be awake.

And as for Bette Midler—her voice still catching as she hugged friend after friend on the chapel steps—she seemed to sum up what everyone else felt but couldn’t quite phrase. “Diane,” she had said earlier, “was extraordinary.” Not in the loud, showy way the word sometimes suggests, but in the way that suggests the rarest gift: to make the ordinary radiant. In her hands, a scarf could be a banner, a pause could be a riot of feeling, a tossed-off line could become a creed. It’s why the room laughed through tears, and why people who never met her left feeling like they had.

There are farewells you remember because of their grandeur, and farewells you remember because of their truth. This one was the latter. No spectacle, no gilding—just friends and family and peers, insisting on the particularity of a woman who refused to be anything but herself. As the last guests slipped into waiting cars and the chapel doors closed with a quiet click, the day settled into the kind of California dusk that Keaton loved to photograph: long shadows, a sky the color of watered watercolor, the first streetlights humming on. Somewhere in that gentle half-light, the industry Keaton helped to shape made a soft promise—to try, at least, to keep faith with the kind of courage she modeled. La-di-da. And onward.