OXT “Who Killed Janet Brown? A 30-Year Search for Answers in a Quiet English Village”

The story begins, as so many true-crime stories do, not with a sensational arrest or a dramatic confession, but with silence. A spring morning in rural Buckinghamshire; a lane bordered by hedgerows; a builder arriving at work to the sound of a house alarm. Within minutes, police would cordon off a farmhouse tucked back from Spriggs Holly Lane in the hamlet of Radnage. Within hours, news would ripple through the county. Within days, a family would be thrust into a long, exhausting vigil for justice that has now stretched across three decades.

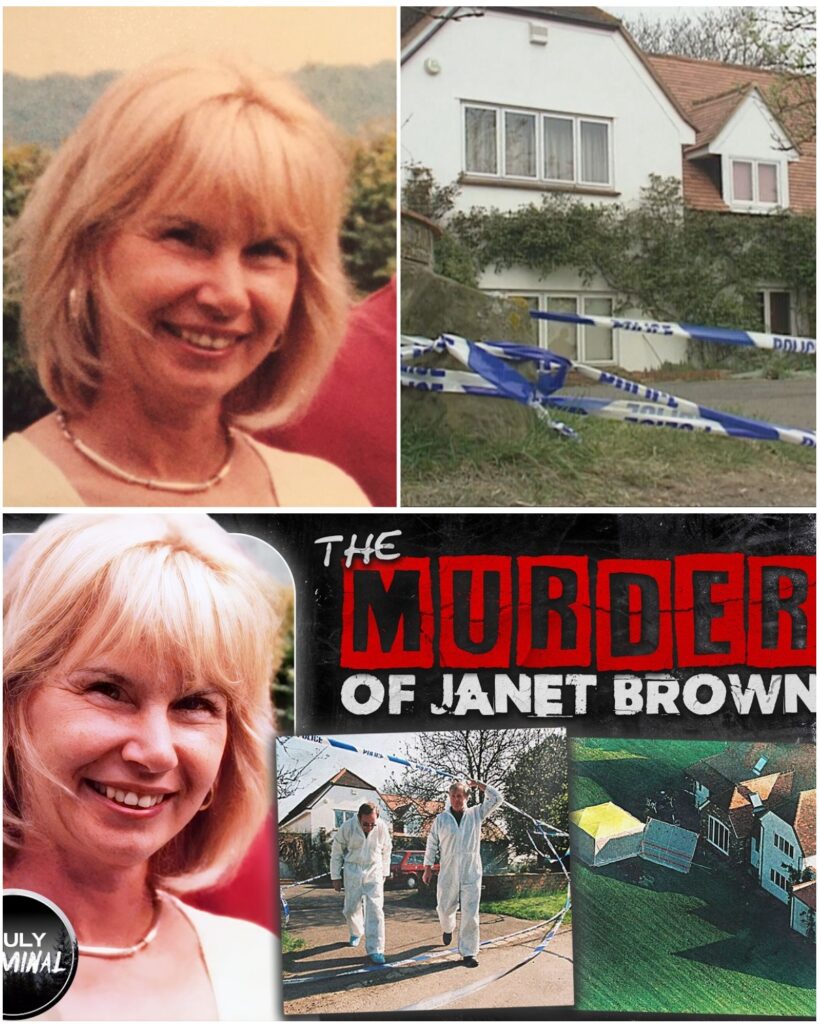

This is the story of Janet Brown—wife, mother, nurse, researcher, neighbor—whose death in April 1995 shocked an area more accustomed to the steady rhythms of the countryside than to major crime. It is also a story about persistence: of investigators who refused to shelve a baffling case, of relatives who have carried their grief with dignity, and of a community that has never stopped hoping that someone, somewhere, will speak.

What follows is a reconstruction meant to engage, not to sensationalize. Certain distressing specifics have been deliberately left out. The aim is to preserve dignity, protect loved ones, and focus on what still matters most: the unanswered questions, the facts that endure, and the slender but real avenues to resolution.

Janet’s World

To understand why the case of Janet Brown has never fully receded from public attention, one must first understand who she was. Born in Southampton, Janet trained as a midwife and later worked in public health and primary care research associated with Oxford University’s John Radcliffe Hospital.

Those who knew her talk about steadiness and kindness: a professional who cared deeply about people; a neighbor who noticed when someone needed a hand; a mother who, in the words of her children, “was always there,” especially when her husband’s international work kept him away.

Janet and her husband, Graeme, were raising three children—Zara, Benedict, and Roxan—at a farmhouse on an 11-acre property set well back from the road. The Browns’ home life was busy but ordinary: school runs, exams, first jobs, travel plans, weekend chores. Friends describe Janet as someone who loved the outdoors and who took pride in the small rituals of family life. If there was a defining feature to her personality it was composure. She preferred peace to drama and reliability to spectacle.

That is, perhaps, part of why what happened in April 1995 still feels so inexplicable. Janet was not involved in disputes. She was not reckless. She was careful—so careful, in fact, that when there were reports of burglaries in the wider area, she joined the local neighborhood watch and made sure the home’s security systems were in working order. She was, by every account, exactly the kind of person who should have been safe in her own house.

The Day Before

Monday, 10 April 1995, unfolded without incident. Janet left work as usual, said her goodbyes, and drove home. The Browns were in the process of selling the house; an offer had been accepted, and the normal bustle of coordinating builders and viewings was in motion.

Roxan, 17, had gone out that afternoon to celebrate a friend’s newly passed driving test. Benedict, 21, was away at university. Zara had recently moved to London for her first job after graduating. Graeme was on a work trip in Switzerland. Janet would be home alone that evening—common enough in a busy family, and unremarkable.

Sometime around 8 p.m., Janet spoke with one of Roxan’s friends on the phone. A builder who was due at the house the next morning—Nick Marshall—called around 8:20 p.m. to confirm arrangements but got no answer. Graeme tried calling at 9:00 p.m. and also could not reach Janet.

A neighbor driving by at roughly 10:00 p.m. heard an alarm sounding, though it was quiet again when she passed later. The home’s system included a pair of panic buttons, one near the bed and one by the front door. Investigators would later determine that the internal alarm continued to ring inside the house even after the external siren had ceased.

The following morning, around 8:00 a.m., Nick arrived with his son to start work. Hearing the alarm, he looked through a window and saw what no one in a peaceful village expects to see. He ran for help and called police. Thames Valley Police responded immediately, and soon an investigation team began the careful, slow work of reconstructing a night that no one could quite explain.

What Police Found—and What They Didn’t

From the outset, the scene presented a puzzle. Entry had been forced via a rear patio door. There were indications that someone had first attempted a neat cut through the glass before resorting to a more destructive method. Items associated with restraint were at the scene, suggesting premeditation.

Several rooms appeared to have been searched. Yet nothing obvious seemed to be missing—no jewelry, no electronics carried away, no cash taken. The overall picture was neither a straightforward burglary nor a spontaneous attack; it looked, rather, like something planned and then carried out in a way that did not fit the typical patterns investigators see.

Detective Superintendent Mike Short, an experienced officer with nearly three decades of service, spoke candidly about his bafflement in the months that followed. This did not appear to be a case in which a criminal assumed a home was empty. Lights were on. A car was visible. Alarms were active.

The intruder (or intruders) came anyway, entered anyway, and—critically—remained in the house long enough to move about after the alarm sounded. That detail alone set this crime apart. As Det. Supt. Short noted at the time, most opportunist burglars flee the moment an alarm is tripped. Whoever came to the Brown residence was not easily scared off.

The Immediate Response

Police launched a comprehensive inquiry. Forensic teams conducted fingertip searches of the property and surrounding fields. The house was examined in microscopic detail. Thousands of lines of inquiry were opened. Officers took around 2,000 witness statements. They canvassed the lanes, pulled traffic observations, cataloged every unusual occurrence neighbors could remember.

Leads emerged and fizzled. A parked car spotted near “the Triangle,” a local landmark by the lane, piqued interest. Anonymous phone messages left for police months later hinted at someone who might know more but never came to anything; the caller was never identified.

A man was arrested the following year on suspicion and interviewed, but the case against him did not hold. Investigators pressed on. The press followed every development. The Brown family, thrust into all the worst parts of public attention, tried to navigate a world that no longer made sense.

The Human Cost

Families confronted with unsolved crimes speak of time in a different way. It does not advance tidily; it loops back. Everyday tasks—the supermarket run, the school pickup, the late-night walk to the kitchen—are haunted by memory.

Zara would later recall those early days when newspapers carried her mother’s photograph and the case dominated local headlines. She remembers panic, sleeplessness, and the way the mind invents noises in the dark. Roxan, younger and still in school, moved to London to live with Zara while she finished her A-levels, commuting back and forth to sit exams. The family never returned to the farmhouse; what had once been a place of comfort no longer felt like home.

It is possible to count police interviews and evidence submissions. It is not possible to tally private grief. The Browns coped as families do: together, imperfectly, resiliently. They worked. They moved house. They made practical changes that anyone would make: added security, changed routines, told people where they were going and when they expected to be back. They also did what families in their position often do: they kept appealing to the public, asking—always asking—for anyone with information, however small, to come forward.

The Five Theories—and Their Limits

From the earliest days, investigators tested several working hypotheses, each of which seemed plausible at first glance and then, upon scrutiny, failed to align with the facts.

A burglary gone wrong? The intruder’s persistence after the alarm sounded argues against the behavior of a typical property crime. The house was searched, but nothing obvious was taken. Why choose a time when the property appeared occupied? Why make so much noise to enter? Why remain?

A contract killing? Professional killers do not generally linger, and they are not likely to spend time moving through a home while alarms ring. The manner of entry and the search behavior also run counter to the stereotype of a clinical, in-and-out operation.

A crime with a sexual motive? Police ruled that out early. There was no evidence to support it.

Industrial espionage connected to Graeme Brown’s scientific work? He was, by all accounts, a respected research chemist. But he himself did not consider this theory plausible, and investigators found nothing to suggest spies in the hedgerows.

A kidnapping attempt that went wrong? There was no indication that anyone tried to remove Janet from the house, no sign of a vehicle positioned for that kind of crime, and no contact consistent with ransom.

In 1996, Det. Supt. Short summarized the problem plainly: every theory contradicted some key fact. The intruder had planned to some degree—bringing tools, choosing a point of entry—yet behaved in ways that defied ordinary criminal logic. Without a clear motive, the investigation lacked the narrative thread that so often guides detectives to a suspect.

A Village Watches and Waits

Radnage is the kind of place where people notice unfamiliar cars. The countryside is open; the lanes are narrow; the same faces pass on their morning walks. After the crime, residents were alert to anything unusual.

Neighbors had already been watchful because of earlier burglaries in the wider area, and practices like noting down number plates and reporting suspicious vehicles were routine. In the weeks after Janet’s death, that collective attentiveness intensified. Police urged anyone who had seen so much as a parked car in an odd spot or a stranger on foot to come forward.

The logic was simple: in a rural area, tiny details matter.

Officers also made a specific appeal about certain items used during the break-in, including distinctive tape and a glass-cutting tool. The thought was that someone might recall a person purchasing such tools together, or a conversation in a shop, or a casual comment that now seemed different in hindsight. Sometimes cases move on such small hinges.

A Breakthrough, of a Kind

For twenty years, the Brown case remained officially unsolved but never dormant. In 2015, Thames Valley Police’s Major Crime Investigation Review Team re-examined the evidence using advances in forensic science that had not been available in the mid-1990s.

Items from the scene were resubmitted to laboratories; processes were repeated with greater sensitivity. The result: a usable DNA profile belonging to a man who was not a member of the Brown family.

This was, at once, a significant step and a frustrating one. On the one hand, it narrowed the field dramatically. DNA is not a theory; it is a fact. On the other hand, when the profile was compared to records in the national database—containing millions of entries—there was no match. Detectives released only the broad contours of what they had found, mindful of protecting the investigation. What they made clear was this: the profile is real, it is probative, and it can easily rule individuals in or out. With public assistance, it could become the keystone to a case that has long lacked one.

What DNA Can—and Cannot—Do

Television has taught us to think of DNA as a magic key that opens every locked door. In practice, it is a powerful tool that still requires context. A profile can eliminate suspects; it can support a strong theory; it can link scenes and objects. But unless it matches someone in an existing database or is voluntarily supplied for comparison, a profile cannot name a person on its own.

That is why detectives have, in recent years, asked the public to come forward not only with names of living individuals who might be relevant, but also with information about people now deceased whose relatives might be willing to provide familial samples. In some cases, modern forensic genealogy—carefully and legally used—has illuminated cases that once seemed insoluble.

Thames Valley Police have screened more than a thousand men to date. Each screening is quiet, methodical, respectful. Each “not a match” narrows the search just a fraction. Each “not a match” also reiterates a different truth: for cases like this one, the decisive clue often resides in memory—something seen, something heard, something said in an unguarded moment long ago.

The Anonymous Voice

One of the odder threads in the Brown investigation emerged about ten months after the crime, when police received two answer-phone messages from a man who did not identify himself. Detectives judged the calls unlikely to be hoaxes. The tone and content suggested knowledge that was not easily guessed from public reporting. An appeal went out for the caller to come forward.

He did not. He has not, to this day. Perhaps he was frightened. Perhaps he was mistaken about some detail and worried about being implicated. Perhaps he has since died. Whatever the reason, those messages now read like a fork in a road not taken: a voice in the dark that might have led somewhere, if only it had stayed on the line.

The Family’s Appeal

Over the years, the Brown family has spoken sparingly and with composure about what they have endured. They describe Janet as a calm, gentle woman who balanced work and family with grace. They speak of nights disrupted by fear and days weighted by the knowledge that someone was responsible and has not yet been named.

They do not speculate publicly about motive. They focus on what they—and detectives—know: that there is a DNA profile; that more than a thousand men have been ruled out; that this case demands, above all, that anyone with knowledge or even suspicion should find a way to share it.

In one public statement marking the twentieth anniversary of the crime, the family put it plainly: “Our mum’s death was planned and devastating. The horror of that night has never left us. We are asking anyone who knows anything, however small, to come forward—anonymously if necessary. Please help us find who did this.” That appeal still stands.

Why the Case Endures

True-crime storytelling often leans into sensational detail. The Brown case resists that treatment. Its power lies not in shock value but in its contradictions. A rural home that did not look empty. A careful person who took reasonable precautions. An intruder who appears to have planned for entry but behaved in ways that make little sense for simple theft.

An alarm that sounded and yet did not scare the person away. Rooms searched and nothing obvious taken. A community on alert, and still no eyewitness who can confidently supply a face or a name. A DNA profile that is ready to close the loop, if only it meets its match.

There is, too, the dissonance between the quiet landscape and the violence of the act. Radnage is the kind of place where time seems to idle. Thirty years later, the rolling fields and long views remain unchanged. It is precisely that sense of continuity that keeps the question alive. If so little else has changed, why should the truth remain hidden?

What Might Move the Case Now

Cold cases turn on three kinds of momentum: scientific, investigative, and human. The first advances through technology—better lab techniques, new databases, refined methods of comparison. The second depends on investigative stamina—teams willing to re-read statements, re-walk scenes, re-evaluate assumptions, and keep filing away the “no’s” until a “yes” arrives. The third—human momentum—is the most unpredictable. It happens when someone remembers, or reconsiders, or finally decides to speak.

For the Brown case, all three forms of momentum are in play. Forensics have already yielded a strong profile. Detectives continue to review material and to test new avenues. What remains uncertain is the human piece: the individual who heard something at a pub one night in 1995; the friend or partner who noticed a person returning home late, agitated, with unexplained cuts or damaged clothing; the shop assistant who sold an odd combination of tools to someone who seemed nervous; the relative who has wondered, privately, about a now-deceased family member’s unexplained behavior in that time period. Any one of those memories might be the spark.

How to Help—Safely, Respectfully

Thames Valley Police encourage information sharing through multiple channels, including the Major Crime Investigation Review Team and Crimestoppers, which allows anonymous tips. The DNA component of the case also means that people can be definitively cleared with minimal disruption.

If you are worried about naming someone who is deceased, police can sometimes work with relatives to obtain comparison samples, always with consent and in accordance with the law. If you fear reprisals or involvement, anonymous routes exist for a reason. What matters is that information moves from private rumination into the hands of people who can test it.

There has also been a reward for information leading to a conviction. Rewards are not, in themselves, solutions. They can, however, prompt someone to step over the threshold from doubt to action. Thirty years is a long time to live with nagging knowledge.

Memory, Justice, and the Long Wait

When a homicide is solved swiftly, communities breathe out. When it is not, the community learns to breathe differently. A long case like this one becomes a kind of civic echo—heard at anniversaries, revisited when new technologies offer hope, amplified when families speak. The goal is not to keep a wound open. It is to refuse forgetting. Justice delayed is not, in fact, justice denied if people keep working at it.

But justice delayed exacts a cost. It asks families to keep answering questions; it asks investigators to keep asking them; it asks neighbors to keep noticing.

The good news, if one can use that phrase in a case like this, is that the Brown investigation is closer to resolution than it has ever been. Thirty years ago, DNA in a case of this kind might have been partial, fragile, or undetectable.

Today, the profile is clean enough to eliminate or implicate individuals with speed and precision. Thirty years ago, an anonymous phone call might have been untraceable, a clue lost to air. Today, a person can contact authorities in multiple ways from multiple places, without risk to themselves, and do so in minutes.

A Closing Word to the Reader

Perhaps you are reading this nowhere near Buckinghamshire. Perhaps you were a child in 1995. Perhaps you have never heard of Radnage. Even so, you might know a person who had a reason to be in that part of England at that time.

You might recognize the way a specific combination of tools—distinctive tape, a glass cutter, restraints—points to a particular trade or shop or habit. You might recall a conversation about a “break-in that went too far,” mentioned offhand long ago. You might be related to someone who once lived in the area and who is no longer alive but left questions in their wake.

If any of those descriptions ring even faintly true, consider this an invitation to act. Reach out to the authorities. Share what you remember. If the person you suspect is gone, ask about lawful ways to compare familial DNA. The officers working this case do not need theories; they need facts—a name, a date, a purchase, a sighting. Those facts may be small. In cold cases, small facts are often decisive.

Thirty Years On

The Buckinghamshire countryside looks much as it did in 1995: quiet lanes, long shadows in late afternoon, the slow conversations of people who have known one another for decades. The Brown family’s life, like every life touched by sudden loss, has been rearranged around an absence. They have carried on with courage. They have kept faith that the system built to provide justice will, eventually, provide it. They have done what is hardest: they have asked, without bitterness, for help.

“Who killed Janet Brown?” is not a rhetorical question or a headline. It is a real question with a real answer. Somewhere, there is a person who knows. Somewhere, there is someone who suspects. Somewhere, there is a memory that would, if spoken, make sense of the puzzle that has resisted solution for thirty years.

That is why this story is being told again—not to dwell on pain, not to peddle fear, but to ask a country that is better connected than ever before to do what only people can do: remember, speak, and help close a circle that has been open for far too long.

If you have information relevant to the investigation, contact Thames Valley Police’s Major Crime Investigation Review Team or Crimestoppers. You can provide details anonymously if necessary. Even a small piece of information can matter. For the Browns, for their neighbors, and for every family navigating the long, patient work of waiting, the difference between almost knowing and finally knowing is everything.